Before Memorial Day, I wrote about three Franklin lads who joined the Army before World War II and were shipped off to the Philippines.

When the war started, they were forced into the Bataan Death March by the Japanese as the world witnessed the events unfold in movie news shorts and on the radio.

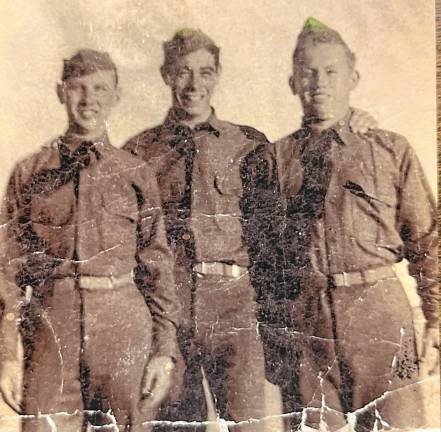

These three buddies were Mike Parchomcik, Mike Concoy and Joe Auche.

Concoy and Auche died, along with many others, in the aptly named Death March. Today they are remembered by streets named after them in Franklin. It is hoped that their memory will continue as the last of the World War II vets pass on.

Parchomcik made it to the prisoner of war camp at Cabanatuan. He later was sent to Japan on a Japanese ship that was transporting prisoners during the war.

These were called “hell ships” because of their horrific conditions, their unmarked status despite carrying prisoners of war, and the likelihood of dying from drowning, suffocation, being caught in explosions or being shot by the guards. More than 100 ships were indeed sunk by U.S. subs or aircraft or perhaps bad weather.

Parchomcik made it, though.

He had to work in coal mines for the enemy under brutal conditions with no end in sight.

In the jubilant triumph of being freed, he then returned to America. Then he re-enlisted.

He did retain some samples of his time in enemy hands:

• Along with the precious photo of the three friends, there is a color photo of himself in formal uniform before the fighting began.

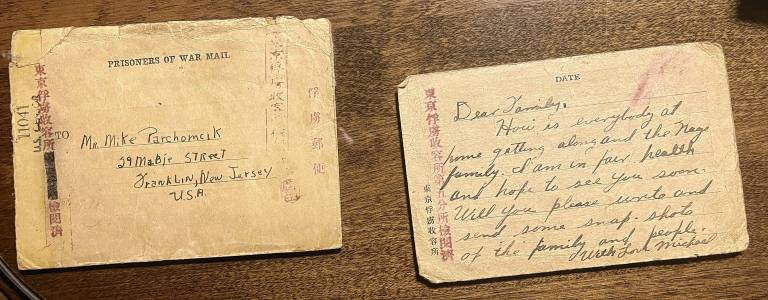

• An envelope, addressed to his father on Mabie Street, and the short note inside: “Dear Family, How is everybody at home getting along and the Hays family. I am in fair health and hope to see you soon. Will you please write and send some snapshots of the family and people. With Love, Michael.”

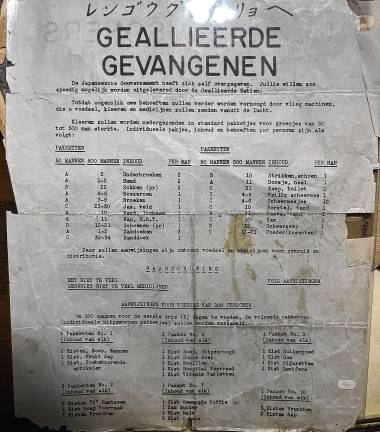

• A flier, retained by Parchomcik at the end of the war in Japan and carried by him on his journey back to America, contains instructions by the defeated Japanese to their war prisoners.

The attached paper is in Dutch and Japanese. Here is the interpretation of the Dutch:

“Allied Prisoners:

“The Japanese government has surrendered. You wish to be handed over to the Allied nations as soon as possible.

“Until that moment, your needs will further be met by aircraft, which will send you food, clothing and medicine from the air.

“Clothing will be sent down in standard packages for groups of 50 to 500 men in strength. Individual packages, contents and needs per person are as follows.”

(The “sent down” in Dutch suggests that these supplies were dropped from Allied planes.)

• The number 467 was Parchomcik’s prisoner-of-war number, sewn onto his clothing and worn every day during his confinement to denote the human within.

It is in awe that we can look at what his family must have treasured when received, and the joy of his return.

These artifacts show us how precious the veterans’ lives are, the brutal conditions that they suffered and the high-risk conditions that they endured.

Thank a vet!

Bill Truran, Sussex County’s historian, may be contacted at billt1425@gmail.com