‘I served my country’

HISTORY. Fifty years after the end of the Vietnam War, local veterans tell of their experiences over there and when they came home.

They were high school graduates. They were young teachers trying to make ends meet for their families. They were grunts, officers and Green Berets. They were at Khe Sanh. They fought at the Tet Offensive. They came to define PTSD.

Today they are grandfathers. They mourn the loss of comrades, of relationships. They always remember. And sometimes they share.

What follows are some of those rare stories.

Albert Bull: What my father could never tell me

Albert Bull of Blooming Grove, N.Y., chose to become a Navy hospital corpsman and physician assistant. Duke University founded the Physician Assistant Program in the mid-1960s by taking advantage of the stream of Army medics and Navy corpsmen returning from Vietnam with medical experience won in the field. The program provided a new force of mid-level medical professionals that helped fill a critical shortage of doctors. Bull’s field experience came during theTet Offensive, a series of surprise attacks by the North Vietnamese army and Vietcong that brought the war to a turning point. Bull joined the Navy Reserves with a six-year commitment and was assigned to a 12-month tour in Vietnam.

I lost my father the day after Christmas of ‘64. I was 17. I grew up as the oldest son and was very close to my father.

My father was in World War II. He served in North Africa for four years and then the invasion of Sicily and into Italy. His company was originally 160 men. At the end of the war, he was one of four left alive and in the field.

I was always asking my father what it was like. What did it feel like being in the situations that you were in?

He never answered. He never told me what it felt like.

And I didn’t know until I got into the service, and until I got to Vietnam, in combat. Not on board ship – I was a Navy corpsman, I was on the ground with the Marines, the Third Marine division in the northern part of South Vietnam. And as such, I participated in combat.

So I served my country, but not as a combat veteran. I chose to be a Navy corpsman for the exact opposite reason – saving lives, not taking lives. I grew up going to church very regularly on my mother’s instructions, and I had 16 or 18 years of perfect attendance at Sunday school.

So the lessons I learned from Sunday school, the Bible, the Protestant religion about not killing and helping your neighbor, and all of the things that go with that – I had in me as an intellectual knowledge. I tried to be a good person and do the right thing. And when it came time in the mid-’60s, with all the conflict and the pros and cons of service to the country, I kind of rode the fence. I served my country but I did not serve my country in an aggressive combat-type of thought line. I served to save lives.

And I went to corps school. I worked in the Philadelphia Naval Hospital. I worked with a doctor, a specialist, on a one-time basis, observing a procedure. And that doctor was called to Bethesda three weeks later to work on the President of the United States.

When I was in Khe Sanh I met a doctor from Brooklyn. I was a New Yorker, so that gave us a special bond. With him being a doctor and with me being a practical nurse, we worked together. I was a high school graduate when I entered the service. But under the doctor’s supervision, I did minor surgery. So when I got home, I was practically a licensed doctor, at minimum a registered nurse. I did things as a Navy corpsman that I had no way of following up with. When I came out of service, the Physician Assistant Program had just started, and it wasn’t a very high priority in the United States.

When I was in Vietnam, I was at first in the infantry. I was hurt and put on light duty. And then I was assigned to an artillery battalion. It turned out to be Khe Sanh Combat Base at the Tet Offensive of 1968. Khe Sanh took the first incoming round, right into our ammunition dump.

But to answer the question that I asked my father about what it’s like? It’s not something that you can tell anybody.

Nobody can tell what it’s like unless you are involved with it and doing it. We do not, as individuals, hunt to kill prey that is also capable of hunting and killing you.

And it’s pretty much like what combat is. I shoot at them and they shoot at me. That’s was what we were doing, back and forth.

And I could not explain that to anybody who has not done it themselves.

For a long time I could not distinguish whether it was my father or Our Father. But I was in a situation where I was so close to booby trap explosives that I did not get injured on, I felt the hand of my father or Our Father protecting me.

It was 20 or more years later, speaking to some people, that I settled in my mind that my father was with me in Vietnam. He protected me. He was with me.

When I came home, the first thing on my mind is that I’m not in a combat zone. I’m not going to be actively hunted. But I had the experience of combat, of seeing people die and seeing people survive – who may be side by side.

Seeing the injuries, and especially treating people in the hospitals, I became a fatalist. There’s a feeling of what will happen will happen. It’s not anything you have control over. You do day by day the best that you can.

That last year I spent in Vietnam, my oldest son was born. He was 11 months old the day I came home. His mother was my high school sweetheart and we lasted a little longer than a year. My time in the service – taking me away from her when the baby was born – she developed a whole new life while I was gone.

Now my son and I are close, though with separate lives, many miles apart. He is a replica of my father. He has the physical characteristics and personal traits that remind me of my father. His word is very important to him. He is very successful in business because he is so honest, so reliable. My father was the same way.

Losing my father when I was 17 was the greatest loss of my life.

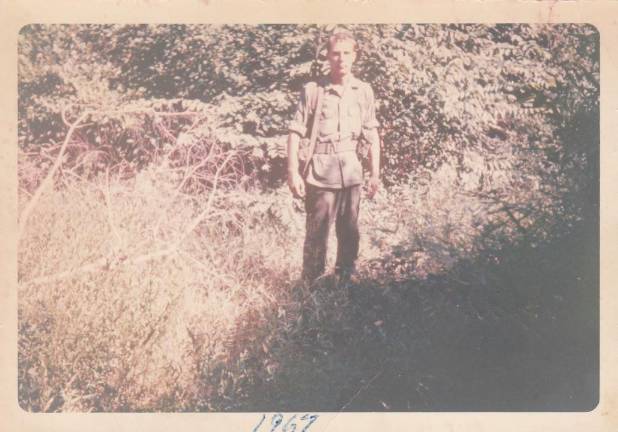

John J. Ruszkiewicz: Gathering intelligence

The following passages are excerpted from My Vietnam Anecdotes (2020, Royal Fireworks Press) by Lt. Col. (Ret.) John J. Ruszkiewicz of Warwick, N.Y.

I served two tours of duty in Vietnam, all of 1966 and all of 1971. On my first tour I was a captain. I spent six months in the Army headquarters in Saigon and six months with the Green Berets (special forces) working out of Nha Trang. I traveled quite a bit, especially during my time with the special forces. Their mission was to organize and train Civilian Irregular Defense Group soldiers, especially ethnic minorities in the central highlands.

I was a major on my second tour and worked as an intelligence advisor in the Mekong Delta. I had operational control over a small platoon of ex-Viet Cong called Kit Carson Scouts. I worked with the CIA often, exploiting information they acquired through their network of sources.

Many have written about the war. I recall General Hal Moor’s We Were Soldiers Once and Young, Mark Bowden’s 1968: Battle of Hue, and Ken Burns’ TV series on Vietnam, to name a few.

My experiences in Vietnam were nowhere near as gruesome and horrifying. I was sent there to do a job and I did the best I could. We all have memories, and mine concerning Vietnam I have compartmentalized into the ones I don’t care to dwell on any longer and those I enjoy thinking about. After all, I lived them, and some make me smile when I think about them. Some of them do not....

In Washington for my daughter’s wedding, I decided to visit the Vietnam memorial. I was advised not to go, but I persisted.

In the registry book I looked for several names and their location on the memorial. To my relief, the name of a young helicopter pilot I knew was not listed in the book. What a relief to know he had survived his tour of Vietnam.

The second was a fellow Green Beret I had known at Fort Bragg. He was one of the earlier casualties of the war. When I found Shotgun’s name.... like a ton of bricks, grief hit me. I ran out bawling my head off.

In combat, there is no room for those feelings. You store them up and release them at some future time.

I will never go back to that memorial.

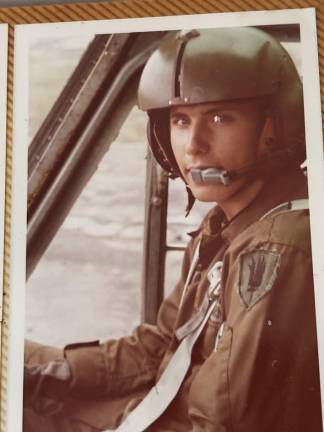

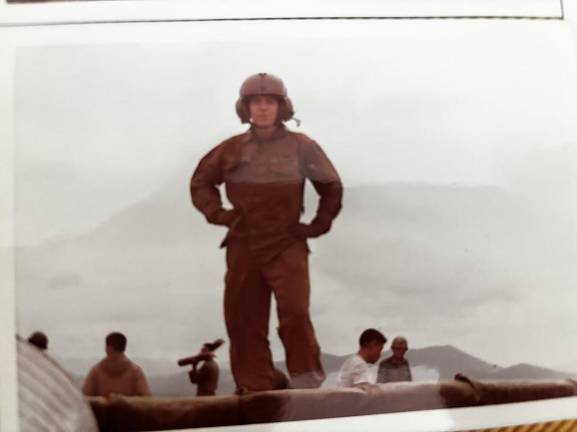

Patrick Shea: Monroe-Woodbury graduate goes from college to hot zone

I served on active duty from October 1970 to July 1973, when the war ended. I was granted an early release due to the end of the war and an excess of pilots. Normally, I would have had to serve six more years.

In 1969, my lottery number was called for the draft. At the time, I was a full-time college student, so my status was deferred. But in spring 1970, I dropped a course and was reclassified as 1A, making me draft-eligible.

Not wanting to be drafted into the infantry, I enter the Army’s Warrant Officer Aviation program.

Over the next two years, I trained at Fort Polk, Fort Walters and Fort Rucker. After graduating from the Army Warrant Officer Aviation Course, I was licensed as a commercial helicopter pilot, qualified to fly both the Huey and the Kiowa, and was quickly deployed to Vietnam.

I arrived in Vietnam on April 6, 1972, at the start of the North Vietnamese Spring Offensive — the most intense fighting in the country since the Tet Offensive of 1968. I was stationed at Lane Army Heliport in Binh Dinh Province, the same area where my cousin was killed in 1968.

Our area of operation spanned from the central coast to the central highlands, an area where significant enemy activity and battles were prevalent. Our unit, the 129th Assault Helicopter Company, lost a number of pilots, crew and aircraft during the first six months of my deployment. The story of our unit during that period is well documented in the book Mission of Honor written by Jim Crigler, a fellow pilot in my unit.

After Vietnam, I was stationed at Fort Lewis, near Seattle. I was granted early release. I returned to school at the University of South Florida in Tampa, the city where I started my career in the financial services industry and remained in the area until 2001, when we moved to Virginia. Since 2007, I’ve lived in Monroe, N.Y., on the homestead my grandfather purchased, and my family has lived in since 1911. I was born and raised here and graduated from Monroe-Woodbury High School in 1969.

As a helicopter pilot in Vietnam, our days were filled with hours of routine boredom followed by moments of sheer terror. It’s those moments of terror that stay with me the most – emergency landings caused by enemy fire, inserting troops in hot landing zones among other combat incidents.

The country’s mood was deeply divided at the time, and anti-war sentiment was high. We didn’t feel welcome coming home. I remember arriving at Travis Air Force Base near San Francisco — many of us changed into civilian clothes immediately, trying to blend in.

At 20 years old, I matured rapidly because of Vietnam. Returning to college afterward, I felt a profound appreciation for the everyday freedoms we often take for granted. I had gone from praying nightly to survive and not have to take a life, to sitting peacefully in a university classroom beside smiling students and beautiful girls. It was a stark contrast that forever changed my perspective.

Having lived and traveled abroad, I know the U.S. isn’t perfect, but it remains the country I love most. I’m grateful to call the Hudson Valley home—its mountains, valleys, trails, lakes and fresh air are where I find peace. No matter where I travel, this is the place I always want to return to.

Everett Cox: Learning the Survival Arts

Everett Cox served in Vietnam with the 245th Surveillance Airplane Company at Marble Mt. Airbase and was an aerial camera specialist.

I enlisted in the U.S. Army on Nov. 25, 1966. I finished my enlistment in August 1969 in Vietnam – but not before a rocket attack altered my consciousness.

A year later, a psychiatrist diagnosed me as paranoid and/or paranoid schizophrenic. I was told it was incurable, that I would get progressively worse, never better, and that I would end my days in a madhouse. I struggled with suicidal depressions and other self-destructive behaviors for the next 40 years.

In 2010, I went to a retreat for veterans at the Omega Institute in the Hudson Valley led by Claude AnShin Thomas, a former U.S. Army helicopter door gunner and crew chief who became a Buddhist monk and led retreats for vets. For the first time, I began to speak and write about my experience in Vietnam.

I mark that as when I began to become a vet. Becoming a vet means owning the experience. I had denied it, avoided it, ran from it. Because I was ashamed of my experience in Vietnam, I did not associate with other vets. I was outwardly silent and isolated, but war was raging internally with guilt, shame and remorse.

A month after that retreat, I heard Dr. Ed Tick speak about PTSD. He had started a veteran aid organization called Soldier’s Heart, which was what PTSD was called after the American Civil War. For the first time I understood my original diagnosis may have been wrong.

I began to attend Warrior Writers workshops in Manhattan. I signed up to create a play with veterans. Each vet was paired with a professional actor. We found a private place to get to know each other, then regrouped and began the “process.” It wasn’t easy. It required a lot of attention. It was a rigorous, often frustrating intellectual and emotional process to stay on track and find the diamond in some very rough shit.

It was a wild and crazy time for this wild and crazy vet, participating in dance workshops, veteran/civilian dialogs, writing workshops and public readings. I became a regular attendee at the NYC Veterans Mental Health Coalition. I began to call these experiences “Survival Arts.”

In 2012, at my third retreat at Omega, a counselor asked me how I was doing. I said I could not stop thinking about suicide, that I had a plan and the means. He urged me to go to the nearest vet center. He gave me a name and a phone number.

I went.

Two years later, I was re-diagnosed with PTS. We have now dropped the “D” for “disorder.” We now say it is not a disorder but a natural response to unnatural violence.

My Survival Arts began when I came home from Vietnam and worked as a laborer. Hard physical work, pick and shovel work, stonework, tree work, helped me manage anger and depression. I worked in a public garden for years. I was a snowmaker at a ski center for many winters. Working with my hands, working out in nature. For more than a year I worked full time with a dozen homeless boys – a powerful emotional experience, a powerful Survival Art.

I became a housepainter, a very meditative work. Another Survival Art.

In 2014, I began work for the New York State Joseph P. Dwyer Veteran Peer Program. I was immersed in veterans’ issues and problems. I did more theater work and have had many pieces of my writing published. Two years ago, my vet counselor said she was taking me out of the high suicide risk category.

As we vets like to say, “So it goes.” Crazy vet. Becoming a vet. Survival Arts.

Jack Crowley: A life of service

Vietnam veteran Jack Crowley, of Sparta, N.J., left his teaching job to spend five and a half years in the Tonkin Gulf, then went on to become a naval commander. While in service he met his wife, Diane Crowley, a retired Navy nurse commander. Crowley’s promotion to naval commander in 1981 capped “15 years of active service and a career that includes 77 months of sea duty, three combat tours and four deployments in the Pacific,” according to a news clipping from that time.

I enlisted at Lakehurst Naval Air Station in 1966 at age 22, during my second year of teaching and coaching at Toms River High School. While I enjoyed teaching and loved coaching gymnastics, two of my teaching colleagues had served: one an early Vietnam-era Green Beret, and the other a Navy Phantom pilot from the Korean War. A third co-teacher, John, had earned his degree after Air Force service. All three were impressive, settled individuals and encouraged me to “go for it.”

Being a young married guy with a son, living on my $5,000 a year salary (minus benefits) was a struggle. We waited for ShopRite’s Friday 39-cents-per-pound sales on meat and were challenged by auto expenses. So I enlisted.

My combined time, calculated by the Navy Personnel Center, was five and a half years in the Vietnam Combat Zone (Tonkin Gulf). I sailed aboard two carriers (Kearsarge, Ranger) and one cruiser (Biddle) as Radio, then Communications Department Head. My rank went from Temporary E-5 in training to commander before retirement. I parlayed my teaching experience into the Navy Reserve’s Training and Administration of Reserves program, so had early command of Navy Reserve Centers when I rotated to shore duty.

Service is a good place to grow up, gain skills and meet life-long friends. You may even, as I did, find a life partner. Diane and I met on a flight to Boston on Alleghany Air (tickets are half-price for those in uniform). She’s also a retired Navy (Nurse) Commander. We have three sons, plus my son from my previous marriage, and live happily home in Sparta.

William Lemanski: No welcome home

Bill Lemanski, of Tuxedo, N.Y., served two tours in Vietnam with an infantry specialty in the central highlands of Pleiku Province. A disturbing incident upon his homecoming remains with him to this day.

I enlisted in the U.S. Army in December 1965 at the age of 18. At that time, I was working in New York City as a junior draftsman. I served two tours in Vietnam with an infantry specialty in the Central Highlands of Pleiku Province.

In 1975, when the war ended, I was working in New York as an engineer designing cabling and control systems for a nuclear generating plant.

The most significant and troubling of my war memories, lasting to this day, was the way the American public treated returning war veterans.

I remember an incident when returning from one of my tours in Vietnam. My buddy and I were passing through the passenger terminal at La Guardia Airport in uniform and a crowd of disheveled young people carrying anti-war signs saw us and began cursing us and attempting to spit on us. This type of conduct was rife across the country at that time. Thankfully, most citizens now have a different attitude towards those who serve in uniform and honor them for their sacrifice and bravery.

I’m early retired from an engineering career in the nuclear industry. Since retiring in 2003, I’ve become a writer.