A killing and its aftermath

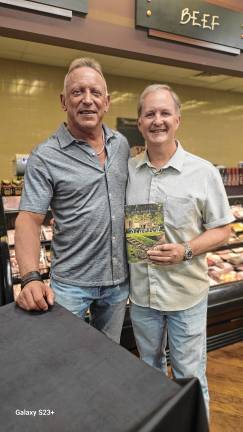

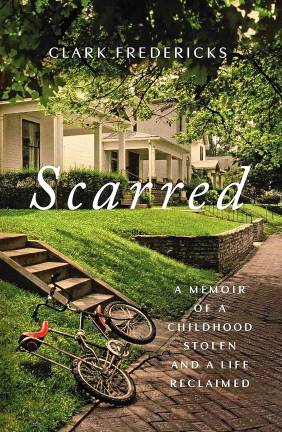

STILLWATER. Fredericks’ book tells about him stabbing the man who abused him, then working to help other victims.

The quiet of this sprawling Sussex County township was broken on June 13, 2012, with the killing of an alleged sexual predator.

A new book tells the story from the point of view of the man wielding the knife.

Clark Fredericks wrote “Scarred: A Memoir of a Childhood Stolen and a Life Redeemed” to tell what he considers the most important story: getting his life back and advocating for changes in the law to provide justice for victims of abuse.

Probably most important of all is Fredericks’ dedication to helping other victims through counseling and his podcast, “FreeLikeMe.”

What happened

Dennis Pegg was a Sussex County sheriff’s officer, Boy Scout leader, and member of the local Kiwanis and the Audubon Society.

Rumors had circulated for some time that he had taken advantage of boys in his charge, at his home and on camping trips, but the only people who knew for sure were those boys.

And they weren’t talking - until the day that Fredericks saw Pegg in a deli with a young boy.

Seeing him with another child brought back memories of his own abuse.

Some time later, he was with his friend Robert Reynolds, and a conversation about a man who had stiffed Fredericks on a motorcycle sale led him to confess what Pegg had done to him.

Reynolds had said a man who stiffed him must be No. 1 on his hit list.

Fredericks admitted that someone else had done something worse.

“Bob was the first person I told,” he said.

Boy Scout knife

In a recent interview, Fredericks said he doesn’t remember whose idea it was for Reynolds to drive him to Pegg’s house, but in less than 15 minutes, they were there.

He didn’t have any plans when he got to the house, but he knew Pegg had a number of guns, so he brought his Boy Scout knife, one Pegg had taught him how to sharpen.

He opened the screen door and stood in the doorway. Pegg looked around and said over his shoulder, “Hey, how are you?”

Fredericks replied, “Let me show you how I am,” and he pulled out the knife.

After stabbing Pegg, he called to Reynolds to bring the car around. “Then I turned back to Pegg and slit his throat,” he said.

When the two men got back to Fredericks’ house, his mother saw that he had blood on his hands and called his sister, Holly, who lived in Califon.

She called her therapist, who called the New Jersey State Police in Augusta and asked for a wellness check on Pegg.

Suicide mission

Fredericks admitted that he had stabbed Pegg.

“I considered it a suicide mission,” he said, thinking that Pegg would have a gun handy and kill him.

He initially was charged with first-degree murder, but Sheriff’s Officer Howie Ryan, who led the crime scene team, told him that his blood was all over the scene and he should keep his mouth shut.

Fredericks said he needed that “smack back to reality.”

After he spent three years in the Sussex County Correctional Facility, Fredericks’ charge was reduced to second-degree manslaughter. He then spent a year in Northern State Prison in Newark.

Reynolds initially was charged with aiding in the killing, but that was downgraded to third-degree hindering an investigation.

Fredericks’ release from prison is where the story really begins, he said.

His niece, Kim Fredericks, who still lives in Stillwater, picked him up and took him for “real food, my parole officer and a new wardrobe.”

A law needed changing

In those years, New Jersey had the tightest statute of limitations on child abuse crimes of any state. People older than 18 had only two years to file charges against their abusers.

While working at the Boat House restaurant in Stillwater, Fredericks became a staunch advocate for changing the law.

The result was the strongest in the nation. Victims now have until age 55 to file charges. In addition, a two-year window was granted for victims of any age to file.

That window was difficult to negotiate. Fredericks remembers a representative of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Camden telling the advocates that they would never get the window, which only energized them to go after it.

Getting the law changed was step one. Step two was finding out how he could help others who went through what he did.

Fredericks worked with NBC’s “Dateline” on a documentary later shown on the Oxygen network. And he appeared on Tamron Hall’s talk show.

Those appearances - and help again from Ryan, the sheriff’s officer who advised him after the killing - led to speaking engagements where he could interact with other victims.

Fredericks has started a podcast, “FreeLikeMe.” He invites former victims who fell into addiction, as he did, to share their trauma.

Now the book tells his story. He is working on scheduling a signing event at the former Presbyterian Church in Stillwater, which is directly opposite Pegg’s former house, in a way bringing the story full circle.

Not all bad

Some aspects of his story are encouraging. He said he was treated very well during the time he was in the Sussex County jail, surrounded by people who had worked with Pegg for years.

While he has nothing good to say about the corrections officers in Newark, he did have a therapist who got him into a group that was “a wonderful experience.”

Fredericks started writing the book while in prison, but when guards tossed his cell, as they did routinely, they discarded three notebooks full of his writing. So he started over.

Since “half the battle” in publishing a book is finding an agent, Fredericks was lucky because he knew someone who set him up with Manhattan agent David Halpern.

After some searching, Halpern found someone interested in the book at Simon & Schuster.

Perhaps the best thing that has happened to Fredericks is reconnecting with Lisa Kaufman. She was a college sweetheart he dated on and off for six years but knew he couldn’t fully commit to because of his trauma.

“It haunted me for 30 years,” he said. “I couldn’t tell her why.”

Feeling that he could never have a relationship with anyone unless he could contact her and explain, he found her.

“We corresponded back and forth and discovered we were still in love.”

He moved to Westchester County, N.Y., to be near her.

“So the guy gets the girl in the end,” he said.